“It was 20 years ago today.” Well, it was actually 50, and it wasn’t today, but on February 9, 1964, The Beatles made their first live television appearance in the United States on the Ed Sullivan Show. That now legendary performance marked the start of the U.S.’s love affair with the four-man band from Liverpool — which before long would capture the minds and hearts of people all over the globe. The world’s fascination with the Fab Four had begun.

Papers, books, web sites — indeed whole careers — have been devoted to the study of The Beatles and everything the band’s members created, sang, uttered, argued about, wore, drank, inhaled, consumed, loved and hated — both collectively and individually — during and after the course of the band’s reign at the top of the charts. Analyses of its lyrics alone form the subject of several books; the words of The Beatles’ songs are seen as providing clues and insights into the minds and mysteries of this legendary quartet about which we can’t seem to know enough.

Glossophilia takes a romp through this most famous garden of prose. Straight from the horses’ mouths, John’s and Paul’s own words (as well as those of George and Ringo) tell some of the stories behind the lyrics and what inspired and fed them. From bus rides to breakfast cereal ads, a cab driver’s photo ID to a beloved pet, acid trips to Disney movies, the stories are endlessly fascinating and sometimes myth-busting. The adventure begins with a look at the “Paul Is Dead” theory and the lyrics that helped fuel this outlandish idea; Glossophilia then journeys through some of the songs — in roughly the order they were written (recording dates are in parentheses) — with comments from the lyricists themselves. By no means an exhaustive survey, this is a selective collection of entertaining insights from the men who gave us some of our favorite songs. Most of the quotes are taken from a handful of publications: a substantial interview given to Playboy magazine in 1980 by John Lennon and Yoko Ono, excerpted in the magazine in January 1981 and later published in full as All We Are Saying by David Sheff in 2000; Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now, the 1998 biography by Barry Miles; and The Beatles Anthology, 2000.

“Paul Is Dead”?

On September 17th, 1969 the Drake Times-Delphic — a college newspaper — published what is widely thought to be the first printed account (or allegation) of Paul McCartney’s supposed death in a car-crash — an urban legend that had first surfaced a couple of years earlier, after McCartney’s car was involved in a crash, and then resurrected itself on the grapevine with more punch and supposed ammunition just two years later. Here are some clues embedded in Beatles song lyrics or in words heard on their recordings that the “PIDers” (believers that “Paul is dead”) pointed to as evidence of his dramatic and subsequently covered-up demise:

A Day in the Life: Its opening line, “Wednesday morning at 5 o’clock as the day begins”, is supposed to describe the day and time of Paul’s fatal accident. And someone in the song “blew his mind out in a car.”

Glass Onion: “Well, here’s another clue for you all; the Walrus was Paul.” Lennon dismissed this line as having no meaning (see below for his explanation). In Roman and Arctic cultures, the walrus is seen as a symbol of death. (True.) A “glass onion” is thought by the PIDers to be an old English term for a see-through coffin. (There doesn’t seem to be any evidence for this.)

While My Guitar Gently Weeps: George apparently sings “Paul, Paul, Paul” at the end of the song. (He’s really just moaning.)

I’m So Tired: The nonsense at the end, played backwards, becomes “Paul is dead, man, miss him, miss him.”

Don’t Pass Me By: Ringo sings “You were in a car crash / And you lost your hair.” This supposedly describes what happened when Paul died.

Good Morning, Good Morning: “Nothing to do to save his life”. And could the title have been a play on the word “mourning”?

Revolution #9: The repeated phrase “Number nine,” when played backwards, becomes “turn me on, dead man” and “cherish the dead”. Much of the recorded conversation in this track is said to provide clues to Paul’s crash and death: here are some of the words that can apparently be heard. “His voice was low and his eyes were high and his eyes were closed.” “His legs were drawn, his hands were tied, his feet were bent and his head was on fire and his glasses were insane. This was the end of his audience.” “My wings are broken and so is my hair. I’m not in the mood for wearing clothing.” Also apparently heard in this section are the sounds of a crash, a fire, sirens, and someone screaming “get [or let] me out.”

Strawberry Fields Forever: It was commonly thought that John says “I buried Paul” at the end of the song. In fact, he’s saying “cranberry sauce” — twice. You can hear this clearly on the Anthology 2 album. Lennon confirms this in his Playboy interview: “I said ‘Cranberry sauce.’ That’s all I said. Some people like ping-pong, other people like digging over graves. Some people will do anything rather than be here now.”

I Am the Walrus: The chanting at the end, when played backwards, becomes “Paul is dead! Ha ha!”

* * *

The Beatles lyrics miscellany — in their own words

PS I Love You (June 1962)

“It’s just an idea for a song really, a theme song based on a letter, like the Paperback Writer idea. It was pretty much mine. I don’t think John had much of a hand in it. There are certain themes that are easier than others to hang a song on, and a letter is one of them. ‘Dear John’ is the other version of it. The letter is a popular theme and it’s just my attempt at one of those. It’s not based in reality, nor did I write it to my girlfriend [Dot Rhone] from Hamburg, which some people think.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Please Please Me (Sep 1962)

“Please Please Me is my song completely. It was my attempt at writing a Roy Orbison song, would you believe it? I wrote it in the bedroom in my house at Menlove Avenue, which was my auntie’s place… I remember the day and the pink coverlet on the bed and I heard Roy Orbison doing Only The Lonely or something. That’s where that came from. And also I was always intrigued by the words of ‘Please, lend me your little ears to my pleas’ – a Bing Crosby song. I was always intrigued by the double use of the word ‘please’. So it was a combination of Bing Crosby and Roy Orbison.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

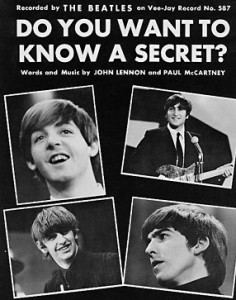

Do You Want to Know a Secret (Feb 1963)

“The idea came from this thing my mother used to sing to me when I was one or two years old, when she was still living with me. It was from a Disney movie: ‘Do you want to know a secret? Promise not to tell? You are standing by a wishing well.’ So, with that in my head, I wrote the song and just gave it to George to sing.” (Lennon, Playboy)

There’s A Place (Feb 1963)

The song was based loosely on the song “Somewhere” from West Side Story, whose soundtrack album McCartney owned.

“In our case the place was in the mind, rather than round the back of the stairs for a kiss and a cuddle. This was the difference with what we were writing: we were getting a bit more cerebral.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

She Loves You (July 1963)

“It was again a she, you, me, I, personal preposition song. I suppose the most interesting thing about it was that it was a message song, it was someone bringing a message. It wasn’t us any more, it was moving off the ‘I love you, girl’ or ‘Love me do’, it was a third person, which was a shift away. ‘I saw her, and she said to me, to tell you, that she loves you, so there’s a little distance we managed to put in it which was quite interesting.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

“I remember it was Paul’s idea: instead of singing ‘I love you’ again, we’d have a third party. That kind of little detail is apparently in his work now where he will write a story about someone and I’m more inclined to just write about myself.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

And I Love Her (Feb 1964)

“The ‘And’ in the title was an important thing. ‘And I Love Her,’ it came right out of left field, you were right up to speed the minute you heard it. The title comes in the second verse and it doesn’t repeat. You would often go to town on the title, but this was almost an aside, ‘Oh… and I love you.'” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

A Hard Day’s Night (April 1964)

“I was going home in the car and Dick Lester suggested the title Hard Day’s Night from something Ringo’d said. I had used it in In His Own Write but it was an off-the-cuff remark by Ringo. You know, one of those malapropisms. A Ringoism, where he said it not to be funny, just said it. So Dick Lester said we are going to use that title, and the next morning I brought in the song.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying by David Sheff)

“So we were sitting around at Twickenham studios having a little brain-storming session; … and we said, ‘Well, there was something Ringo said the other day’… He said after a concert, ‘Phew, it’s been a hard day’s night.’ John and I went, ‘What? What did you just say?’ He said, ‘I’m bloody knackered, man, it’s been a hard day’s night.’ ‘Hard day’s night! Fucking brilliant! How does he think of ’em? Woehayy!'” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Eight Days A Week (Oct 1964)

“I remember writing that with John, at his place in Weybridge, from something said by the chauffeur who drove me out there. … I usually drove myself there, but the chauffeur drove me out that day and I said, ‘How’ve you been?’ – ‘Oh, working hard,’ he said, ‘working eight days a week.’ I had never heard anyone use that expression, so when I arrived at John’s house I said, ‘Hey, this fella just said, “eight days a week”.’ John said, ‘Right – “Ooh I need your love, babe…” and we wrote it We were always quick to write. We would write on the spot. I would show up, looking for some sort of inspiration; I’d either get it there, with John, or I’d hear someone say something.” (McCartney, Anthology)

You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away (Feb 1965)

“You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away is my Dylan period. It’s one of those that you sing a bit sadly to yourself, ‘Here I stand, head in hand…’ I’d started thinking about my own emotions. I don’t know when exactly it started, like I’m A Loser or Hide Your Love Away, those kind of things. Instead of projecting myself into a situation, I would try to express what I felt about myself, which I’d done in my books. I think it was Dylan who helped me realise that — not by any discussion or anything, but by hearing his work.” (Lennon, Anthology)

Note the similarities between the opening lines of this song and those of Dylan’s “I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Have Never Met)”:

Lennon-McCartney: “Here I stand, head in hand / Turn my face to the wall / If she’s gone I can’t go on / Feeling two foot small”

Dylan: “I can’t understand, she let go of my hand / And left me here facing the wall / I’d sure like to know why she did go / But I can’t get close to her at all”

* * *

Apparently, during the recording session Lennon sang ‘two foot small’ instead of ‘two foot tall’ by mistake. “Let’s leave that in, actually,” he told his childhood friend Pete Shotton. “All those pseuds will really love it.”

It’s Only Love (June 1965)

“It’s Only Love is mine. I always thought it was a lousy song. The lyrics were abysmal. I always hated that song.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

“If a lyric was really bad we’d edit it, but we weren’t that fussy about it, because it’s only a rock ‘n’ roll song. I mean, this is not literature.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Drive My Car (Oct 1965)

“The lyrics were disastrous and I knew it… This is one of the songs where John and I came nearest to having a dry session. The lyrics I brought in were something to do with golden rings, which is always fatal. ‘Rings’ is fatal anyway, ‘rings’ always rhymes with ‘things’ and I knew it was a bad idea. I came in and I said, ‘These aren’t good lyrics but it’s a good tune.’ … Well, we tried, and John couldn’t think of anything, and we tried and eventually it was, ‘Oh let’s leave it, let’s get off this one.’ ‘No, no. We can do it, we can do it.’ So we had a break, maybe had a cigarette or a cup of tea, then we came back to it, and somehow it became ‘drive my car’ instead of ‘gold-en rings’, and then it was wonderful because this nice tongue-in-cheek idea came and suddenly there was a girl there, the heroine of the story, and the story developed and had a little sting in the tail like Norwegian Wood had, which was ‘I actually haven’t got a car, but when I get one you’ll be a terrific chauffeur.’ (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

‘”Drive my car’ was an old blues euphemism for sex, so in the end all is revealed. Black humour crept in and saved the day. It wrote itself then. I find that very often, once you get the good idea, things write themselves.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

In My Life (Oct 1965)

“For In My Life, I had a complete set of lyrics after struggling with a journalistic vision of a trip from home to downtown on a bus naming every sight. It became In My Life, which is a remembrance of friends and lovers of the past. Paul helped with the middle eight musically. But all lyrics written, signed, sealed, and delivered. And it was, I think, my first real major piece of work. Up till then it had all been sort of glib and throwaway. And that was the first time I consciously put my literary part of myself into the lyric. Inspired by Kenneth Alsopf [sic], the British journalist, and Bob Dylan. …

“I think In My Life was the first song that I wrote that was really, consciously about my life, and it was sparked by a remark a journalist and writer in England made after In His Own Write came out. I think In My Life was after In His Own Write… But he said to me, ‘Why don’t you put some of the way you write in the book, as it were, in the songs? Or why don’t you put something about your childhood into the songs?’ Which came out later as Penny Lane from Paul – although it was actually me who lived in Penny Lane – and Strawberry Fields.

“In My Life started out as a bus journey from my house on 250 [sic] Menlove Avenue to town, mentioning every place I could remember. And it was ridiculous. This is before even Penny Lane was written and I had Penny Lane, Strawberry Fields, Tram Sheds – Tram Sheds are the depot just outside of Penny Lane – and it was the most boring sort of ‘What I Did On My Holidays Bus Trip’ song and it wasn’t working at all. I cannot do this! I cannot do this! But then I laid back and these lyrics started coming to me about the places I remember.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown) (Oct 1965)

“I came in and he had this first stanza, which was brilliant: ‘I once had a girl, or should I say, she once had me.’ That was all he had, no title, no nothing. I said, ‘Oh yes, well, ha, we’re there.’ And it wrote itself. Once you’ve got the great idea, they do tend to write themselves, providing you know how to write songs. So I picked it up at the second verse, it’s a story. It’s him trying to pull a bird, it was about an affair. John told Playboy that he hadn’t the faintest idea where the title came from but I do. Peter Asher had his room done out in wood, a lot of people were decorating their places in wood. Norwegian wood. It was pine really, cheap pine. But it’s not as good a title, Cheap Pine, baby… So she makes him sleep in the bath and then finally in the last verse I had this idea to set the Norwegian wood on fire as revenge, so we did it very tongue in cheek. She led him on, then said, ‘You’d better sleep in the bath’. In our world the guy had to have some sort of revenge. It could have meant I lit a fire to keep myself warm, and wasn’t the decor of her house wonderful? But it didn’t, it meant I burned the fucking place down as an act of revenge, and then we left it there and went into the instrumental.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Nowhere Man (Oct 1965)

“I was just sitting, trying to think of a song, and I thought of myself sitting there, doing nothing and going nowhere. Once I’d thought of that, it was easy. It all came out. No, I remember now, I’d actually stopped trying to think of something. Nothing would come. I was cheesed off and went for a lie down, having given up. Then I thought of myself as Nowhere Man – sitting in his nowhere land.” (Lennon, The Beatles by Hunter Davies)

“When I came out to write with him the next day, he was kipping on the couch, very bleary-eyed. It was really an anti-John song. He told me later, he didn’t tell me then, he said he’d written it about himself, feeling like he wasn’t going anywhere. I think it was actually about the state of his marriage. It was in a period where he was a bit dissatisfied with what was going on; however, it led to a very good song. He treated it as a third-person song, but he was clever enough to say, ‘Isn’t he a bit like you and me?’ — ‘Me’ being the final word.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

We Can Work It Out (Oct 1965)

“In We Can Work It Out, Paul did the first half, I did the middle eight. But you’ve got Paul writing, ‘We can work it out, we can work it out’ – real optimistic, y’know, and me impatient: ‘Life is very short and there’s no time for fussing and fighting, my friend.'” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

“The lyrics might have been personal. It is often a good way to talk to someone or to work your own thoughts out. It saves you going to a psychiatrist, you allow yourself to say what you might not say in person.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Michelle (Nov 1965*)

Written with help from Jan, the wife of Ian Vaughan, an old school friend of McCartney’s who introduced him to Lennon.

“I said, ‘I like the name Michelle. Can you think of anything that rhymes with Michelle, in French?’ And she [Jan] said, ‘Ma belle.’ I said, ‘What’s that mean?’ ‘My beauty.’ I said, ‘That’s good, a love song, great.’ We just started talking, and I said, ‘Well, those words go together well, what’s French for that? Go together well.’ ‘Sont les mots qui vont très bien ensemble.’ I said, ‘All right, that would fit.’ And she told me a bit how to pronounce it, so that was it. I got that off Jan, and years later I sent her a cheque around. I thought I better had because she’s virtually a co-writer on that. From there I just pieced together the verses.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

* McCartney started writing Michelle in 1959

Eleanor Rigby (April 1966)

“While I was fiddling on a chord some words came out: ‘Dazzie-de-da-zu picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been…’ This idea of someone picking up rice after a wedding took it in that poignant direction, into a ‘lonely people’ direction.” (McCartney, Anthology)

Got To Get You Into My Life (April 1966)

“Got To Get You Into My Life was one I wrote when I had first been introduced to pot. I’d been a rather straight working-class lad but when we started to get into pot it seemed to me to be quite uplifting… I didn’t have a hard time with it and to me it was mind-expanding, literally mind-expanding. … So Got To Get You Into My Life is really a song about that, it’s not to a person, it’s actually about pot. It’s saying, I’m going to do this. This is not a bad idea. So it’s actually an ode to pot, like someone else might write an ode to chocolate or a good claret.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Paperback Writer (April 1966)

“You knew, the minute you got there, cup of tea and you’d sit and write, so it was always good if you had a theme. I’d had a thought for a song and somehow it was to do with the Daily Mail so there might have been an article in the Mail that morning about people writing paperbacks. Penguin paperbacks was what I really thought of, the archetypal paperback. … I arrived at Weybridge and told John I had this idea of trying to write off to a publishers to become a paperback writer, and I said, ‘I think it should be written like a letter.’ I took a bit of paper out and I said it should be something like ‘Dear Sir or Madam, as the case may be…’ and I proceeded to write it just like a letter in front of him, occasionally rhyming it. And John, as I recall, just sat there and said, ‘Oh, that’s it,’ ‘Uhuh,’ ‘Yeah.’ I remember him, his amused smile, saying, ‘Yes, that’s it, that’ll do.’ Quite a nice moment: ‘Hmm, I’ve done right! I’ve done well!’ And then we went upstairs and put the melody to it.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Yellow Submarine (May 1966)

“I was thinking of it as a song for Ringo, which it eventually turned out to be, so I wrote it as not too rangey in the vocal. I just made up a little tune in my head, then started making a story, sort of an ancient mariner, telling the young kids where he’d lived and how there’d been a place where he had a yellow submarine. It’s pretty much my song as I recall, written for Ringo in that little twilight moment. I think John helped out; the lyrics get more and more obscure as it goes on but the chorus, melody and verses are mine. There were funny little grammatical jokes we used to play. It should have been ‘Everyone of us has all he needs’ but Ringo turned it into ‘everyone of us has all we need.’ So that became the lyric. It’s wrong, but it’s great. We used to love that.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

She Said She Said (June 1966)

“It’s an interesting track. … That was written after an acid trip in LA during a break in The Beatles’ tour where we were having fun with The Byrds and lots of girls. Some from Playboy, I believe. Peter Fonda came in when we were on acid and he kept coming up to me and sitting next to me and whispering, ‘I know what it’s like to be dead.’ … He was describing an acid trip he’d been on. We didn’t want to hear about that! We were on an acid trip and the sun was shining and the girls were dancing and the whole thing was beautiful and Sixties, and this guy – who I really didn’t know; he hadn’t made Easy Rider or anything – kept coming over, wearing shades, saying, ‘I know what it’s like to be dead,’ and we kept leaving him because he was so boring! And I used it for the song, but I changed it to ‘she’ instead of ‘he’. It was scary. You know, a guy… when you’re flying high and [whispers] ‘I know what it’s like to be dead, man.’ I remembered the incident. Don’t tell me about it! I don’t want to know what it’s like to be dead!” (Lennon, Playboy)

Strawberry Fields Forever (Nov 1966)

Playboy: “What about the chant at the end of the song: ‘Smoke pot, smoke pot, everybody smoke pot’?”

Lennon: “No, no, no. I had this whole choir saying, ‘Everybody’s got one, everybody’s got one.’ But when you get 30 people, male and female, on top of 30 cellos and on top of the Beatles’ rock ‘n roll rhythm section, you can’t hear what they’re saying.”

Playboy: “What does ‘everybody got’?”

Lennon: “Anything. You name it. One penis, one vagina, one asshole — you name it.”

* * *

“Strawberry Fields is a real place. After I stopped living at Penny Lane, I moved in with my auntie who lived in the suburbs in a nice semidetached place with a small garden and doctors and lawyers and that ilk living around… not the poor slummy kind of image that was projected in all the Beatles stories. In the class system, it was about half a class higher than Paul, George and Ringo, who lived in government-subsidized housing. We owned our house and had a garden. They didn’t have anything like that. Near that home was Strawberry Fields, a house near a boys’ reformatory where I used to go to garden parties as a kid with my friends Nigel and Pete. We would go there and hang out and sell lemonade bottles for a penny. We always had fun at Strawberry Fields. So that’s where I got the name. But I used it as an image. Strawberry Fields forever.” (Lennon, Playboy)

“The second line [sic] goes, ‘No one I think is in my tree.’ Well, what I was trying to say in that line is ‘Nobody seems to be as hip as me, therefore I must be crazy or a genius.’ It’s the same problem as I had when I was five: ‘There is something wrong with me because I seem to see things other people don’t see. Am I crazy, or am I a genius?’ … What I’m saying, in my insecure way, is ‘Nobody seems to understand where I’m coming from. I seem to see things in a different way from most people.'” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

Penny Lane (Dec 1966)

“When I came to write it, John came over and helped me with the third verse, as often was the case. We were writing childhood memories: recently faded memories from eight or ten years before, so it was a recent nostalgia, pleasant memories for both of us. All the places were still there, and because we remembered it so clearly we could have gone on.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

“It’s part fact, part nostalgia for a great place – blue suburban skies, as we remember it, and it’s still there. And we put in a joke or two: ‘Four of fish and finger pie.’ The women would never dare say that. Except to themselves. Most people wouldn’t hear it, but ‘finger pie’ is just a nice little joke for the Liverpool lads who like a bit of smut.” (McCartney, Anthology)

“We were often answering each other’s songs so it might have been my version of a memory song but I don’t recall. It was childhood reminiscences: there is a bus stop called Penny Lane. There was a barber shop called Bioletti’s with head shots of the haircuts you can have in the window and I just took it all and arted it up a little bit to make it sound like he was having a picture exhibition in his window. It was all based on real things; there was a bank on the corner so I imagined the banker, it was not a real person, and his slightly dubious habits and the little children laughing at him, and the pouring rain. The fire station was a bit of poetic licence; there’s a fire station about half a mile down the road, not actually in Penny Lane, but we needed a third verse so we took that and I was very pleased with the line ‘It’s a clean machine’. I still like that phrase, you occasionally hit a lucky little phrase and it becomes more than a phrase. So the banker and the barber shop and the fire station were all real locations.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

A Day in the Life (Jan 1967)

“A Day In The Life – that was something. I dug it. It was a good piece of work between Paul and me. I had the ‘I read the news today’ bit, and it turned Paul on. Now and then we really turn each other on with a bit of song, and he just said ‘yeah’ – bang, bang, like that. It just sort of happened beautifully.” (Lennon, Rolling Stone)

“Just as it sounds: I was reading the paper one day and I noticed two stories. One was the Guinness heir who killed himself in a car. That was the main headline story. He died in London in a car crash. On the next page was a story about 4000 holes in Blackburn, Lancashire. In the streets, that is. They were going to fill them all. Paul’s contribution was the beautiful little lick in the song ‘I’d love to turn you on.’ I had the bulk of the song and the words, but he contributed this little lick floating around in his head that he couldn’t use for anything. I thought it was a damn good piece of work.” (Lennon, Playboy)

“The verse about the politician blowing his mind out in a car we wrote together. It has been attributed to Tara Browne, the Guinness heir, which I don’t believe is the case, certainly as were were writing it, I was not attributing it to Tara in my head. In John’s head it might have been. In my head I was imagining a politician bombed out on drugs who’d stopped at some traffic lights and didn’t notice that the lights had changed. The ‘blew his mind’ was purely a drugs reference, nothing to do with a car crash. … [Re. the middle section — “Woke up, fell out of bed”] “It was another song altogether but it happened to fit. It was just me remembering what it was like to run up the road to catch a bus to school, having a smoke and going into class. It was a reflection of my schooldays. I would have a Woodbine, somebody would speak and I’d go into a dream.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Being For The Benefit of Mr Kite! (Feb 1967)

“The whole song is from a Victorian poster, which I bought in a junk shop. It is so cosmically beautiful. It’s a poster for a fair that must have happened in the 1800s. Everything in the song is from that poster, except the horse wasn’t called Henry. Now, there were all kinds of stories about Henry the Horse being heroin. I had never seen heroin in that period. No, it’s all just from that poster. The song is pure, like a painting, a pure watercolour.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

Good Morning Good Morning (Feb 1967)

“Good Morning is mine. It’s a throwaway, a piece of garbage, I always thought. The ‘Good morning, good morning’ was from a Kellogg’s cereal commercial. I always had the TV on very low in the background when I was writing and it came over and then I wrote the song.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

The Kellogg’s jingle was “Good morning, good morning / The best to you each morning. /

Sunshine breakfast, Kellogg’s Corn Flakes / Crisp and full of fun.”

I Am the Walrus (Sep 1967*)

The song references another Beatles song: “See how they fly like Lucy in the sky.”

“The first line was written on one acid trip one weekend. The second line was written on the next acid trip the next weekend, and it was filled in after I met Yoko. Part of it was putting down Hare Krishna. All these people were going on about Hare Krishna, Allen Ginsberg in particular. The reference to ‘Element’ry penguin’ is the elementary, naive attitude of going around chanting, ‘Hare Krishna,’ or putting all your faith in any one idol. I was writing obscurely, à la Dylan, in those days.” … “It actually was fantastic in stereo, but you never hear it all. There was too much to get on. It was too messy a mix. One track was live BBC Radio– Shakespeare or something*– I just fed in whatever lines came in.” (Lennon, Playboy)

“It’s from ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter.’ ‘Alice in Wonderland.’ To me, it was a beautiful poem. It never dawned on me that Lewis Carroll was commenting on the capitalist and social system. I never went into that bit about what he really meant, like people are doing with the Beatles’ work. Later, I went back and looked at it and realized that the walrus was the bad guy in the story and the carpenter was the good guy. I thought, Oh, shit, I picked the wrong guy. I should have said, ‘I am the carpenter.’ But that wouldn’t have been the same, would it? (singing) ‘I am the carpenter….'” (Lennon, Playboy)

“‘Walrus’ is just saying a dream – the words don’t mean a lot. People draw so many conclusions and it’s ridiculous… What does it really mean, ‘I am the eggman’? It could have been the pudding basin for all I care. It’s not that serious.” (Lennon, Anthology)

“You know, you just stick a few images together, thread them together, and you call it poetry. Well, maybe it is poetry. But I was just using the mind that wrote In His Own Write to write that song. There was even some live BBC radio on one track, y’know. They were reciting Shakespeare or something and I just fed whatever lines were on the radio into the song.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

* * *

Wanting to include nonsense verse in the song, Lennon asked his old childhood friend Pete Shotton to remember nursery rhymes they had sung as kids to work into the lyrics. Shotton offered this: “Yellow matter custard, green slop pie / all mixed together with a dead dog’s eye. / Slap it on a butty, ten foot thick, / then wash it all down with a cup of cold sick.” This is how it ended up in Lennon’s song: “Yellow matter custard dripping from a dead dog’s eye.” “Let the fuckers work that one out,” Lennon remarked.

* * *

As for the first line of the song, “I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together”, many believe that this was taken from the British folk song “Marching to Pretoria,” which dates back to the Boer Wars of the 19th century and is in turn said to be an Anglicized version of the 1865 American Civil War marching song “Marching Through Georgia” by Henry Clay Work. The folk song has several different incarnations, one of whose first lines is said to be “I’m with you and you’re with me and so we are all together,” which does seem to foretell Lennon’s slightly more convoluted lyric. When The Weavers sang and recorded a version of the song in the ’60s, the lyrics didn’t contain this line (according to LyricWiki and YouTube); neither did the Smothers Brothers‘, nor the version recorded by Josef Marais and Miranda; and neither did the one recorded on Zonophone in about 1902 by Ian Colquhoun (whose title was “Marching ON Pretoria”), which is similar to the versions mentioned above.

According to Shmoop.com, “The Beatles themselves always said any link between their song and “Marching to Pretoria” was bogus. Still, the two lyrics are remarkably similar. Perhaps John Lennon had heard the folk song as a child, and one of his later acid trips subconsciously brought it all back to him. Who knows, really? Lennon also mentioned in an interview that he once penned a few lyrics while listening to police sirens outside his London flat: “I had this idea of doing a song that was a police siren, but it didn’t work in the end (sings like a siren) ‘I-am-he-as-you-are-he-as…’ You couldn’t really sing the police siren.” Meanwhile, fellow Beatle George Harrison questioned any attempt to find deep meanings or profound references in the lyrics: “People don’t understand. In John’s song, ‘I Am The Walrus’ he says: ‘I am he as you are he as you are me.’ People look for all sorts of hidden meanings. It’s serious, but it’s also not serious. It’s true, but it’s also a joke.” See you in Pretoria, then?”

* * *

The BBC banned broadcasts of the song because of the use of the phrases “pornographic priestess” and “let your knickers down”.

* I Am The Walrus was written in August 1967

Lovely Rita (Feb 1967)

“There was a story in the paper about ‘Lovely Rita’, the meter maid. She’s just retired as a traffic warden. The phrase ‘meter maid’ was so American that it appealed, and to me a ‘maid’ was always a little sexy thing: ‘Meter maid. Hey, come and check my meter, baby.’ I saw a bit of that, and then I saw that she looked like a ‘military man’.” (McCartney, Anthology)

Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds (Feb 1967)

“My son Julian came in one day with a picture he painted about a school friend of his named Lucy. He had sketched in some stars in the sky and called it ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,’ Simple.” (Lennon, Playboy)

“The images were from ‘Alice in Wonderland.’ It was Alice in the boat. She is buying an egg and it turns into Humpty Dumpty. The woman serving in the shop turns into a sheep and the next minute they are rowing in a rowing boat somewhere and I was visualizing that. There was also the image of the female who would someday come save me… a ‘girl with kaleidoscope eyes’ who would come out of the sky. It turned out to be Yoko, though I hadn’t met Yoko yet. So maybe it should be ‘Yoko in the Sky with Diamonds.'” (Lennon, Playboy)

“A song like ‘Got to Get You Into My Life,’ that’s directly about pot, although everyone missed it at the time. ‘Day Tripper,’ that’s one about acid (LSD). ‘Lucy in the Sky,’ that’s pretty obvious. There’s others that make subtle hints about drugs, but, you know, it’s easy to overestimate the influence of drugs on the Beatles’ music.” (McCartney, Uncut magazine, 2004)

“I showed up at John’s house and he had a drawing Julian had done at school with the title ‘Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds’ above it. Then we went up to his music room and wrote the song, swapping psychedelic suggestions as we went. I remember coming up with ‘cellophane flowers’ and ‘newspaper taxis’ and John answered with things like ‘kaleidoscope eyes’ and ‘looking glass ties’. We never noticed the LSD initial until it was pointed out later – by which point people didn’t believe us.” (McCarney, Anthology)

With a Little Help From My Friends (March 1967)

“This is Paul, with a little help from me. ‘What do you see when you turn out the light/ I can’t tell you, but I know it’s mine…’ is mine.” (Lennon, Playboy)

“This was written out at John’s house in Weybridge for Ringo; we always liked to do one for him and it had to be not too much like our style. … In this case, it was a slightly more mature song, which I always liked very much. I remember giggling with John as we wrote the lines ‘What do you see when you turn out the light? I can’t tell you but I know it’s mine.’ It could have been him playing with his willie under the covers, or it could have been taken on a deeper level; this was what it meant but it was a nice way to say it, a very non-specific way to say it. I always liked that.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Magical Mystery Tour (April 1967)

“Magical Mystery Tour was co-written by John and I, very much in our fairground period. One of our great inspirations was always the barker. ‘Roll up! Roll up!’ The promise of something: the newspaper ad that says ‘guaranteed not to crack’, the ‘high class’ butcher, ‘satisfaction guaranteed’ from Sgt Pepper. ‘Come inside,’ ‘Step inside, Love’; you’ll find that pervades a lot of my songs. If you look at all the Lennon-McCartney things, it’s a thing we do a lot. … Because those were psychedelic times it had to become a magical mystery tour, a little bit more surreal than the real ones to give us a licence to do it. But it employs all the circus and fairground barkers, ‘Roll up! Roll up!’, which was also a reference to rolling up a joint. We were always sticking those little things in that we knew our friends would get; veiled references to drugs and to trips. ‘Magical Mystery Tour is waiting to take you away,’ so that’s a kind of drug, ‘it’s dying to take you away’ so that’s a Tibetan Book of the Dead reference. We put all these words in and if you were just an ordinary person, it’s a nice bus that’s waiting to take you away, but if you’re tripping, it’s dying, it’s the real tour, the real magical mystery tour. We stuck all that stuff in for our ‘in group’ of friends really.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

The Fool on the Hill (Sep 1967)

“The Fool On The Hill was mine and I think I was writing about someone like Maharishi. His detractors called him a fool. Because of his giggle he wasn’t taken too seriously. It was this idea of a fool on the hill, a guru in a cave, I was attracted to.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Across the Universe (Feb 1968)

“I was lying next to my first wife in bed, you know, and I was irritated. She must have been going on and on about something and she’d gone to sleep and I’d kept hearing these words over and over, flowing like an endless stream. I went downstairs and it turned into sort of a cosmic song rather than an irritated song; … But the words stand, luckily, by themselves. They were purely inspirational and were given to me as boom! I don’t own it, you know; it came through like that. I don’t know where it came from, what meter it’s in, and I’ve sat down and looked at it and said, ‘Can I write another one with this meter?’ It’s so interesting: ‘Words are flying [sic] out like [sings] endless rain into a paper cup, they slither while they pass, they slip away across the universe.’ Such an extraordinary meter and I can never repeat it! It’s not a matter of craftsmanship; it wrote itself. It drove me out of bed. I didn’t want to write it, I was just slightly irritable and I went downstairs and I couldn’t get to sleep until I put it on paper, and then I went to sleep.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

“It’s one of the best lyrics I’ve written. In fact, it could be the best. It’s good poetry, or whatever you call it, without chewin’ it. See, the ones I like are the ones that stand as words, without melody. They don’t have to have any melody, like a poem, you can read them.” (Lennon, Rolling Stone, 1970)

According to BeatlesBible, “part of the song’s chorus – ‘Jai guru deva, om’ – is a Sanskrit phrase which roughly translates as ‘Victory to God divine’. It was likely inspired by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, whom The Beatles had met in August 1967. The Maharishi’s spiritual master was called Guru Dev. ‘Jai’ is a Hindi word meaning ‘long live’ or ‘victory’, and ‘om’ is a sacred syllable in the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist religions.”

Lady Madonna (Feb 1968)

“The original concept was the Virgin Mary but it quickly became symbolic of every woman; the Madonna image but as applied to ordinary working class woman. It’s really a tribute to the mother figure, it’s a tribute to women. Your Mother Should Know is another. I think women are very strong, they put up with a lot of shit, they put up with the pain of having a child, of raising it, cooking for it, they are basically skivvies a lot of their lives, so I always want to pay a tribute to them.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Blackbird (June 1968)

“I had in mind a black woman, rather than a bird. Those were the days of the civil rights movement, which all of us cared passionately about, so this was really a song from me to a black woman, experiencing these problems in the States: ‘Let me encourage you to keep trying, to keep your faith, there is hope.’ As is often the case with my things, a veiling took place so, rather than say ‘Black woman living in Little Rock’ and be very specific, she became a bird, became symbolic, so you could apply it to your particular problem.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Hey Jude (July 1968)

“I thought, as a friend of the family, I would motor out to Weybridge and tell them that everything was all right: to try and cheer them up, basically, and see how they were. I had about an hour’s drive. I would always turn the radio off and try and make up songs, just in case… I started singing: ‘Hey Jules – don’t make it bad, take a sad song, and make it better…’ It was optimistic, a hopeful message for Julian: ‘Come on, man, your parents got divorced. I know you’re not happy, but you’ll be OK.’ … I eventually changed ‘Jules’ to ‘Jude’. One of the characters in Oklahoma is called Jud, and I like the name.” (McCartney, Anthology)

Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da (July 1968)

“I had a friend called Jimmy Scott who was a Nigerian conga player, who I used to meet in the clubs in London. He had a few expressions, one of which was, ‘Ob la di ob la da, life goes on, bra’. I used to love this expression… He sounded like a philosopher to me. He was a great guy anyway and I said to him, ‘I really like that expression and I’m thinking of using it,’ and I sent him a cheque in recognition of that fact later because even though I had written the whole song and he didn’t help me, it was his expression. … It’s a very me song, in as much as it’s a fantasy about a couple of people who don’t really exist, Desmond and Molly. I’m keen on names too. Desmond is a very Caribbean name.” (McCartney, Anthology)

Revolution (July 1968)

“I wanted to put out what I felt about revolution. I thought it was time we fucking spoke about it, the same as I thought it was about time we stopped not answering about the Vietnamese war when we were on tour with Brian Epstein and had to tell him, ‘We’re going to talk about the war this time, and we’re not going to just waffle.’ I wanted to say what I thought about revolution. … I had been thinking about it up in the hills in India. I still had this ‘God will save us’ feeling about it, that it’s going to be all right. That’s why I did it: I wanted to talk, I wanted to say my piece about revolution. I wanted to tell you, or whoever listens, to communicate, to say ‘What do you say? This is what I say.'” (Lennon, Rolling Stone, 1970)

While My Guitar Gently Weeps (July 1968)

“I wrote While My Guitar Gently Weeps at my mother’s house in Warrington. I was thinking about the Chinese I Ching, the Book of Changes… The Eastern concept is that whatever happens is all meant to be, and that there’s no such thing as coincidence – every little item that’s going down has a purpose. … While My Guitar Gently Weeps was a simple study based on that theory. I decided to write a song based on the first thing I saw upon opening any book – as it would be a relative to that moment, at that time. I picked up a book at random, opened it, saw ‘gently weeps’, then laid the book down again and started the song.” (Harrison, Anthology)

Dear Prudence (Aug 1968)

“Dear Prudence is me. Written in India. A song about Mia Farrow’s sister, who seemed to go slightly barmy, meditating too long, and couldn’t come out of the little hut that we were livin’ in. They selected me and George to try and bring her out because she would trust us. If she’d been in the West, they would have put her away. … We got her out of the house. She’d been locked in for three weeks and wouldn’t come out, trying to reach God quicker than anybody else. That was the competition in Maharishi’s camp: who was going to get cosmic first. What I didn’t know was I was already cosmic.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

Rocky Raccoon (Aug 1968*)

“Rocky Raccoon is quirky, very me. I like talking blues so I started off like that, then I did my tongue-in-cheek parody of a western and threw in some amusing lines. I just tried to keep it amusing, really; it’s me writing a play, a little one-act play giving them most of the dialogue. Rocky Raccoon is the main character, then there’s the girl whose real name was Magill, who called herself Lil, but she was known as Nancy. … There are some names I use to amuse, Vera, Chuck and Dave or Nancy and Lil, and there are some I mean to be serious, like Eleanor Rigby, which are a little harder because they have to not be joke names. In this case Rocky Raccoon is some bloke in a raccoon hat, like Davy Crockett. The bit I liked about it was him finding Gideon’s Bible and thinking, Some guy called Gideon must have left it for the next guy. I like the idea of Gideon being a character. You get the meaning and at the same time get in a poke at it. All in good fun. And then of course the doctor is drunk.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

“Paul [wrote it]. Couldn’t you guess? Would I go to all that trouble about Gideon’s Bible and all that stuff?” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

* McCartney wrote Rocky Raccoon early in 1968

Glass Onion (Sep 1968)

Lennon deliberately and provocatively inserted references to other Beatles songs into this one, “I Am The Walrus”, “Strawberry Fields Forever”, “Lady Madonna”, “The Fool On The Hill” and “Fixing A Hole”.

“That’s me, just doing a throwaway song, à la “Walrus”, à la everything I’ve ever written. I threw the line in—’the Walrus was Paul’—just to confuse everybody a bit more. … It could’ve been ‘The fox terrier is Paul,’ you know. I mean, it’s just a bit of poetry. I was having a laugh because there’d been so much gobbledygook about Pepper—play it backwards and you stand on your head and all that.” … “Yeah. That line was a joke, you know. That line was put in partly because I was feeling guilty because I was with Yoko, and I knew I was finally high and dry. In a perverse way, I was sort of saying to Paul, ‘Here, have this crumb, have this illusion, have this stroke… because I’m leaving you.'” (Lennon, Playboy)

Happiness Is a Warm Gun (Sep 1968)

“No, it’s not about heroin. A gun magazine was sitting there with a smoking gun on the cover and an article that I never read inside called ‘Happiness Is a Warm Gun.’ I took it right from there. I took it as the terrible idea of just having shot some animal.” (Playboy)

“George Martin showed me the cover of a magazine that said, ‘Happiness is a warm gun’. I thought it was a fantastic, insane thing to say. A warm gun means you’ve just shot something.” (Lennon, Anthology)

Piggies (Sep 1968*)

“Piggies is a social comment. I was stuck for one line in the middle until my mother came up with the lyric, ‘What they need is a damn good whacking’ which is a nice simple way of saying they need a good hiding. It needed to rhyme with ‘backing,’ ‘lacking,’ and had absolutely nothing to do with American policemen or Californian shagnasties!” (Harrison)

* Harrison started writing Piggies in 1966

Julia (Oct 1968)

“Julia was my mother. But it was sort of a combination of Yoko and my mother blended into one. That was written in India. On the White Album. And all the stuff on the White Album was written in India while we were supposedly giving money to Maharishi, which we never did. We got our mantra, we sat in the mountains eating lousy vegetarian food and writing all those songs. We wrote tons of songs in India.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

Martha My Dear (Oct 1968)

“It’s a communication of some sort of affection but in a slightly abstract way – ‘You silly girl, look what you’ve done,’ all that sort of stuff. These songs grow. Whereas it would appear to anybody else to be a song to a girl called Martha, it’s actually a dog, and our relationship was platonic, believe me.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

“She was a dear pet of mine. I remember John being amazed to see me being so loving to an animal. He said, ‘I’ve never seen you like that before.’ I’ve since thought, you know, he wouldn’t have. It’s only when you’re cuddling around with a dog that you’re in that mode, and she was a very cuddly dog.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill (Oct 1968)

“Oh, that was written about a guy in Maharishi’s meditation camp who took a short break to go shoot a few poor tigers, and then came back to commune with God. There used to be a character called Jungle Jim and I combined him with Buffalo Bill. It’s a sort of teenage social-comment song and a bit of a joke.” (Lennon, Playboy)

Get Back (Jan 1969)

Lennon: “I’ve always thought there was this underlying thing in Paul’s ‘Get Back.’ When we were in the studio recording it, every time he sang the line ‘Get back to where you once belonged,’ he’d look at Yoko.”

Playboy:”Are you kidding?”

Lennon: “No. But maybe he’ll say I’m paranoid. You know, he can say, ‘I’m a normal family man, those two are freaks.’ That’ll leave him a chance to say that one.”

* * *

“When we were doing Let It Be, there were a couple of verses to Get Back which were actually not racist at all – they were anti-racist. There were a lot of stories in the newspapers then about Pakistanis crowding out flats – you know, living 16 to a room or whatever. So in one of the verses of Get Back, which we were making up on the set of Let It Be, one of the outtakes has something about ‘too many Pakistanis living in a council flat’ – that’s the line. Which to me was actually talking out against overcrowding for Pakistanis… If there was any group that was not racist, it was the Beatles. I mean, all our favourite people were always black. We were kind of the first people to open international eyes, in a way, to Motown.” (McCartney, Rolling Stone, 1986)

Let It Be (Jan 1969)

“One night during this tense time I had a dream I saw my mum, who’d been dead 10 years or so. And it was so great to see her because that’s a wonderful thing about dreams: you actually are reunited with that person for a second; there they are and you appear to both be physically together again. It was so wonderful for me and she was very reassuring. In the dream she said, ‘It’ll be all right.’ I’m not sure if she used the words ‘Let it be’ but that was the gist of her advice, it was, ‘Don’t worry too much, it will turn out OK.’ It was such a sweet dream I woke up thinking, Oh, it was really great to visit with her again. I felt very blessed to have that dream. So that got me writing the song Let It Be. I literally started off ‘Mother Mary’, which was her name, ‘When I find myself in times of trouble’, which I certainly found myself in. The song was based on that dream.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Octopus’s Garden (April 1969)

“I wrote Octopus’s Garden in Sardinia. Peter Sellers had lent us his yacht and we went out for the day… I stayed out on deck with [the captain] and we talked about octopuses. He told me that they hang out in their caves and they go around the seabed finding shiny stones and tin cans and bottles to put in front of their cave like a garden. I thought this was fabulous, because at the time I just wanted to be under the sea too. A couple of tokes later with the guitar – and we had Octopus’s Garden!” (Starr, Anthology)

You Never Give Me Your Money (May 1969)

“This was me directly lambasting Allen Klein’s attitude to us: no money, just funny paper, all promises and it never works out. It’s basically a song about no faith in the person, that found its way into the medley on Abbey Road. John saw the humour in it.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Carry That Weight (July 1969)

“I’m generally quite upbeat but at certain times things get to me so much that I just can’t be upbeat any more and that was one of the times. We were taking so much acid and doing so much drugs and all this Klein shit was going on and getting crazier and crazier and crazier. Carry that weight a long time: like for ever! That’s what I meant.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Come Together (July 1969)

“Come together is me, writing obscurely around an old Chuck Berry thing. I left the line in “Here comes old flat-top.” It is nothing like the Chuck Berry song, but they took me to court because I admitted the influence once years ago. I could have changed it to “Here comes old iron-face,” but the song remains independent of Chuck Berry or anyone else on earth. … The thing was created in the studio. It’s gobbledygook; “Come Together” was an expression that Tim Leary had come up with for his attempt at being president or whatever he wanted to be, and he asked me to write a campaign song. I tried and I tried, but I couldn’t come up with one. But I came up with this, “Come Together,” which would’ve been no good to him — you couldn’t have a campaign song like that, right? Leary attacked me years later, saying I ripped him off. It’s just that it turned into “Come Together.” What am I going to do: give it to him?” (Lennon, Playboy)

Here Comes The Sun (July 1969)

“Here Comes The Sun was written at the time when Apple was getting like school, where we had to go and be businessmen: ‘Sign this’ and ‘Sign that’. Anyway, it seems as if winter in England goes on forever; by the time spring comes you really deserve it. So one day I decided I was going to sag off Apple and I went over to Eric Clapton’s house. The relief of not having to go and see all those dopey accountants was wonderful, and I walked around the garden with one of Eric’s acoustic guitars and wrote Here Comes The Sun.” (Harrison, Anthology)

Maxwell’s Silver Hammer (July 1969)

“Maxwell’s Silver Hammer was my analogy for when something goes wrong out of the blue, as it so often does, as I was beginning to find out at that time in my life. I wanted something symbolic of that, so to me it was some fictitious character called Maxwell with a silver hammer. I don’t know why it was silver, it just sounded better than Maxwell’s hammer. It was needed for scanning. We still use that expression even now when something unexpected happens.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

Polythene Pam (July 1969)

That was me, remembering a little event with a woman in Jersey, and a man who was England’s answer to Allen Ginsberg, who gave us our first exposure – this is so long – you can’t deal with all this. You see, everything triggers amazing memories. I met him when we were on tour and he took me back to his apartment and I had a girl and he had one he wanted me to meet. He said she dressed up in polythene, which she did. She didn’t wear jackboots and kilts, I just sort of elaborated. Perverted sex in a polythene bag. Just looking for something to write about.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

She Came In Through the Bathroom Window (July 1969)

“That was written by Paul when we were in New York forming Apple, and he first met Linda. Maybe she’s the one who came in the window. She must have. I don’t know. Somebody came in the window.” (Lennon, Playboy)

McCartney was in a taxi heading to JFK airport at the end of their New York trip, and he still hadn’t written a final verse for the song. He noticed on the cab driver’s police ID on the dashboard a photograph of the driver and the name Eugene Quits above the words “New York Police Dept”.

“So I got ‘So I quit the police department’, which are part of the lyrics to that. This was the great thing about the randomness of it all. If I hadn’t been in this guy’s cab, or if it had been someone else driving, the song would have been different.” (McCartney, Many Years From Now)

The End (July 1969)

“That’s Paul again, the unfinished song, right? We’re on Abbey Road. Just a piece at the end. He had a line in it [sings] ‘And in the end, the love you get is equal to the love you give [sic],’ which is a very cosmic, philosophical line. Which again proves that if he wants to, he can think.” (Lennon, All We Are Saying)

* * *

On John and Paul working together on song-writing

(Lennon in the Playboy interview): “I always had an easier time with lyrics, though Paul is quite a capable lyricist who doesn’t think he is. So he doesn’t go for it. Rather than face the problem, he would avoid it. ‘Hey Jude’ is a damn good set of lyrics. I made no contribution to the lyrics there. And a couple of lines he has come up with show indications of a good lyricist. But he just hasn’t taken it anywhere. Still, in the early days, we didn’t care about lyrics as long as the song had some vague theme… she loves you, he loves him, they all love each other. It was the hook, line and sound we were going for. That’s still my attitude, but I can’t leave lyrics alone. I have to make them make sense apart from the songs.”

Playboy: “What’s an example of a lyric you and Paul worked on together?”

Lennon: “In ‘We Can Work It Out,’ Paul did the first half, I did the middle-eight. But you’ve got Paul writing, ‘We can work it out/We can work it out’ –real optimistic, y’ know, and me, impatient: ‘Life is very short and there’s no time/For fussing and fighting, my friend….'”

Playboy: “Paul tells the story and John philosophizes.”

Lennon: “Sure. Well, I was always like that, you know. I was like that before the Beatles and after the Beatles. I always asked why people did things and why society was like it was. I didn’t just accept it for what it was apparently doing. I always looked below the surface.”

Playboy: “When you talk about working together on a single lyric like ‘We Can Work It Out,’ it suggests that you and Paul worked a lot more closely than you’ve admitted in the past. Haven’t you said that you wrote most of your songs separately, despite putting both of your names on them?”

Lennon: “Yeah, I was lying. (laughs) It was when I felt resentful, so I felt that we did everything apart. But, actually, a lot of the songs we did eyeball to eyeball.”

* * *

Further miscellany:

“Copulation” rather than “compilation”?

The Beatles released their first four singles on the tiny indie label Vee-Jay. When Capitol Records tried to sue Vee-Jay to obtain the rights, Vee-Jay hurriedly put together a concept album that contained the four Beatles songs and eight tracks by Frank Ifield. The record production was rushed, and the LP sleeve declared that the label presented the “copulation” (rather than “compilation”) with pride. A cautionary tale for record labels everywhere: don’t forget to proofread.

* * *

* ‘I Am The Walrus’ features a sampled recording of a passage from a BBC production of Shakespeare’s King Lear. The passage reads:

Slave, thou hast slain me. Villain, take my purse.

If ever thou wilt thrive, bury my body

And give the letters which you find’st about me

To Edmund, Earl of Gloucester. Seek him out

Upon the English party. O, untimely death!

Death!

I know thee well: a serviceable villain,

As duteous to the vices of thy mistress

As badness would desire.

What, is he dead?

Sit you down, father. Rest you.