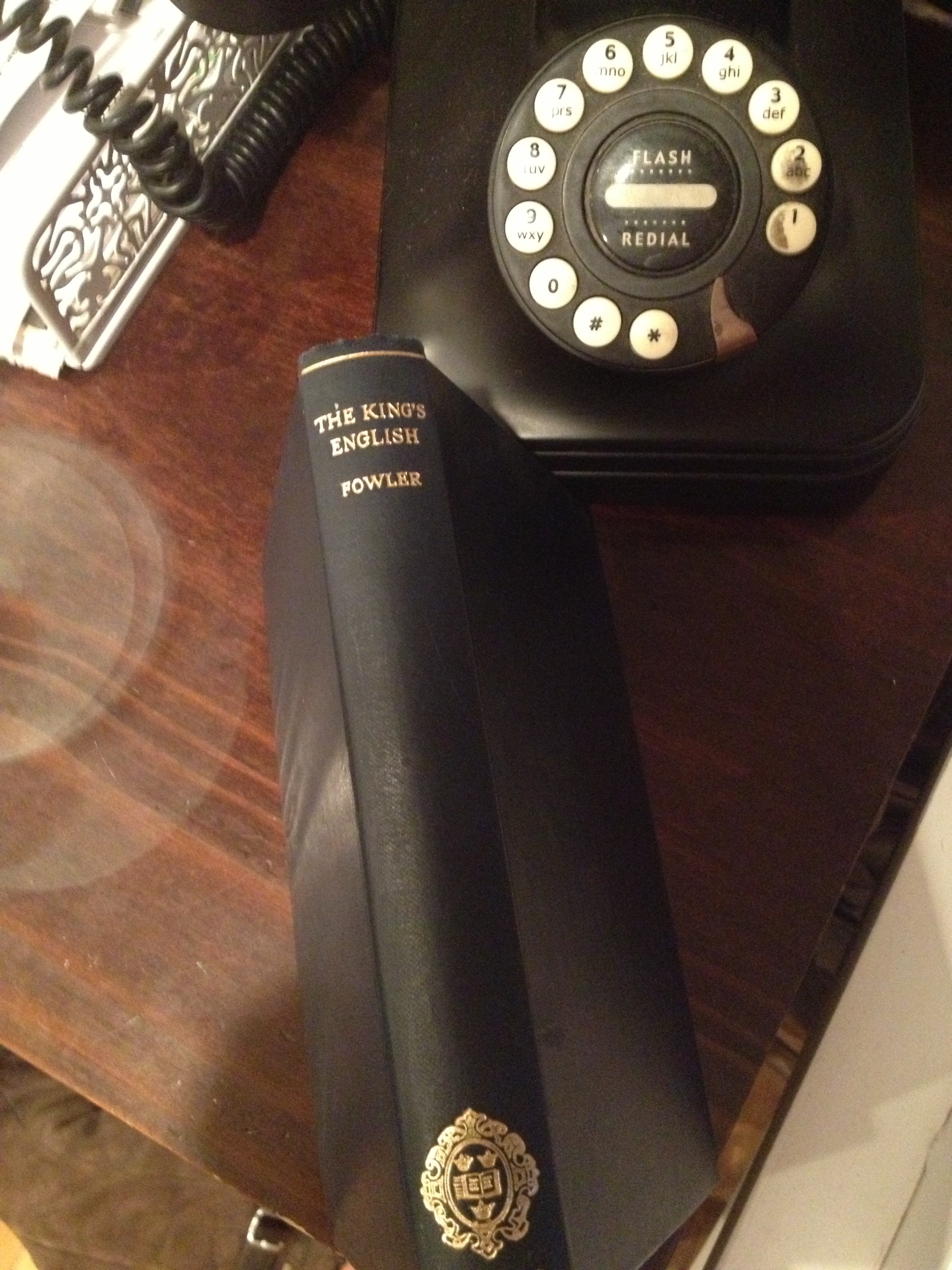

Fowler & Fowler’s complex article on prepositions in their book The King’s English (first published in 1906) is worth reading if only for the opening paragraph. Though characteristically pompous in tone, the introduction can be read as a more general treatise on language and writing, with its assertion that a true command and understanding of preposition usage (read language) is acquired not from the study of dictionaries and grammars, but by sheer instinct, feel, and “good reading with the idiomatic eye open”. More than a century after these words were set down in their formal Edwardian prose, they remain as wise and pertinent today, and probably ring true for many modern editors, linguists, language commentators — and writers themselves — who understand that good writing and language composition are elusive skills that can’t easily be taught or explained.

“In an uninflected language like ours these [prepositions] are ubiquitous, and it is quite impossible to write tolerably without a full knowledge, conscious or unconscious, of their uses. Misuse of them, however, mostly results not in what may be called in the fullest sense blunders of syntax, but in offences against idiom. It is often impossible to convince a writer that the preposition he has used is a wrong one, because there is no reason in the nature of things, in logic, or in the principles of universal grammar (whichever way it may be put), why that preposition should not give the desired meaning as clearly as the one that we tell him he should have used. Idioms are special forms of speech that for some reason, often inscrutable, have proved congenial to the instinct of a particular language. To neglect them shows a writer, however good a logician he may be, to be no linguist — condemns him, from that point of view, more clearly than grammatical blunders themselves. But though the subject of prepositions is thus very important, the idioms in which they appear are so multitudinous that it is hopeless to attempt giving more than the scantiest selection; this may at least put writers on the guard. Usages of this sort cannot be acquired from dictionaries and grammars, still less from a treatise like the present, not pretending to be exhaustive; good reading with the idiomatic eye open is essential. We give a few examples of what to avoid.”