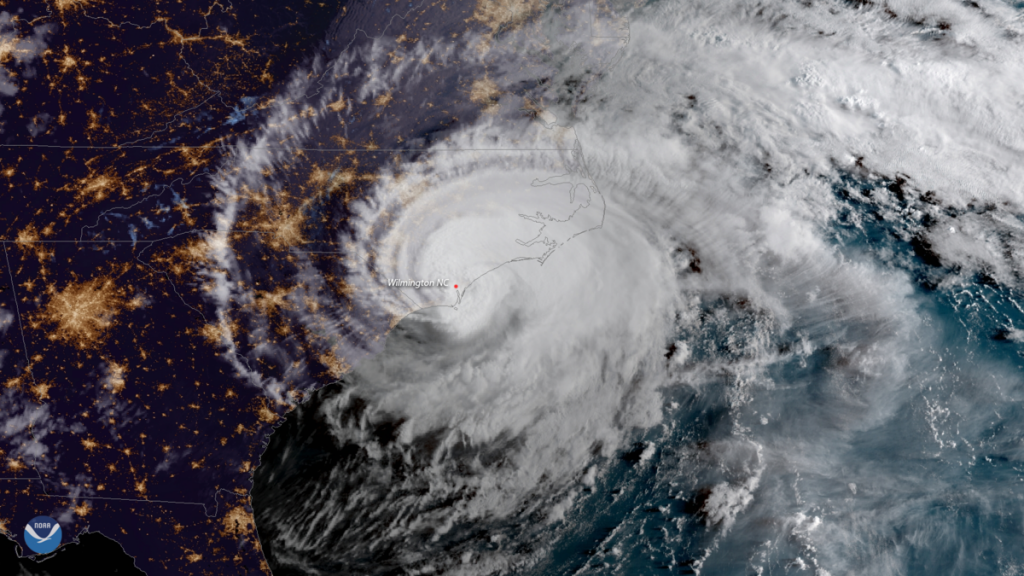

Hurricane Florence makes landfall / Wikimedia CommonsHurricane names are curious — they’re often so strangely obscure. How are they named, and who names them? Why do they have names at all? And is there ever a downside to naming these mega-storms? It might not be good news for a few sorry souls …

A long time ago, meteorologists realized that naming tropical storms and hurricanes helps people to remember the approaching storms and to communicate about them more effectively — especially if hundreds of widely scattered stations, coastal bases and ships at sea are exchanging detailed storm information. So hurricane names keep everyone safer if and when a particular storm strikes a coast. These weather experts assign names to hurricanes according to a formal list of names that’s approved before the start of each hurricane season; this practice was started by the U.S. National Hurricane Center back in the early 1950s. Nowadays, the World Meteorological Organization generates and maintains those approved lists of hurricane names, which are recycled every six years. (Occasionally a storm is so deadly or costly that the future use of its name for a different storm is considered to be inappropriate for reasons of sensitivity; if and when that occurs, the offending name is stricken from the list by the WMO committee and another name is selected to replace it. A lot of names have been retired since the lists were created — from Agnes to Wilma, and including many common names in between.) And in case you’re wondering who’s coming up in 2020, we’ll be meeting — approaching the Atlantic coast — Arthur, Bertha, Cristobal, Dolly, Edouard, Fay, Gonzalo, Hanna, Isaias, Josephine, Kyle, Laura, Marco, Nana, Omar, Paulette, Rene, Sally, Teddy, Vicky, and Wilfred; coming in across the north Pacific will be Amanda, Boris, Cristina, Douglas, Elida, Fausto, Genevieve, Hernan, Iselle, Julio, Karina, Lowell, Marie, Norbert, Odalys, Polo, Rachel, Simon, Trudy, Vance, Winnie, Xavier, Yolanda, and Zeke).

So hurricanes having names seems to be a Good Thing — and not just because the media can make memorable news stories and subeditors can craft snappy headlines: if anything those opportunities are helpful in effective storm preparation.

However, for some people the christening of a hurricane — and the sheer fact of its naming — can spell bad news. Read the small print in this (very typical) travel insurance policy document below, noting the sentences I’ve bolded:

The Insurer will pay a benefit, up to the maximum shown on the Schedule

of Coverages and Services, if the Insured is prevented from or unable to

continue taking his/her Trip due to the following Unforeseen events:”(a) Sickness, Accidental Injury or death of the Insured, Traveling Companion,

Family Member or Business Partner; which results in medically imposed

restrictions as certified by a Physician at the time of Loss preventing your

continued participation in the Trip[…]

(k) Hurricane warning causing cancellation of travel. Claims are not

payable if a hurricane is foreseeable prior to an Insured’s Effective Date.

A hurricane is foreseeable on the date it becomes a named storm. The

Insurer will not pay any benefits 30 calendar days after the incident

occurs.”

So when you’ve booked your dream vacation and forked out for your travel insurance, you probably want to hope and pray that names such as Isaias, Fausto and Odalys don’t bust out of obscurity. ‘Cos if Fausto’s winds blow, they might well blow in more ways than one …

***