Content warnings and advisories aren’t always as explicit as they should be, given the explicit material they’re designed to protect our kids against. Often couched in ambiguous terms, they can leave much to the imagination or to broad interpretation — with sometimes dubious or downright silly results.

The ESRB (Entertainment Software Ratings Board) says that its ratings “provide concise and objective information about the content in video games and apps so consumers, especially parents, can make informed choices.” For games in its “Everyone 10+” category, it warns that the content “may contain … mild language and/or minimal suggestive themes.” Isn’t “mild language” what a toddler speaks when she’s just getting beyond the babbling stage? And as for “minimal suggestive themes”, are we talking about American works of art from the ’60s and early ’70s, or sparse interior decors?

A common warning for parents is that “mild peril” is contained in children’s movies. Is there really such a thing as “mild peril”? Peril, according to most dictionaries, means “serious and immediate danger”. Can serious and immediate danger be mild?

The Classification Board in Australia (where, incidentally, the censorship of video games and internet sites is said to be the strictest in the western world) classifies all material shown in movies, TV and videos. Its “M” rated material is “recommended for people with a mature perspective but is not deemed too strong for younger viewers. Language is moderate in impact.” How do I know if I or my child — or my spouse or parent, for that matter — have a mature enough perspective to view said M movie? And if its language is only moderate in impact, should we be looking for another movie with a better screenplay?

Here’s another good one: “adult situations”. To quote Calvin and Hobbes (the cartoon characters created by Bill Watterson): Calvin: The TV listings say this movie has “adult situations.” What are adult situations? Hobbes: Probably things like going to work, paying bills and taxes, taking responsibilities… Calvin: Wow, they don’t kid around when they say “for mature audiences.”

According to the MPAA classification system, one of the criteria for the R rating is “pervasive language”. The new movie Nebraska is rated R “for some language”. Don’t most movie screenplays nowadays have “pervasive language” or “some language”? I thought they all did, at least since talkies were invented. Screenwriters beware: you might just write and rate yourself out of a job.

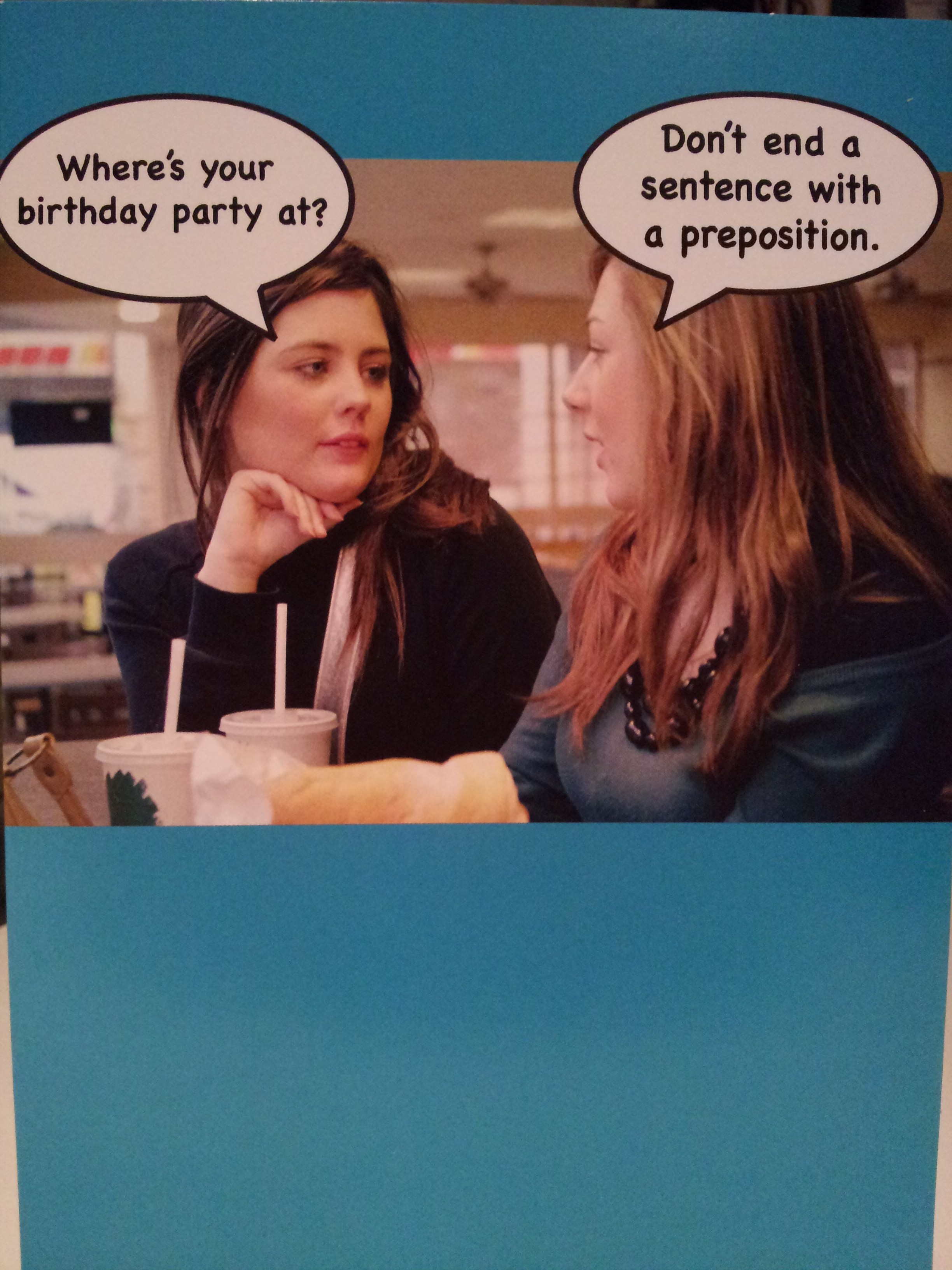

“Contains behaviour which could be imitated” is one of the BBC’s online content advisories. Well, first of all it’s mildly perilous grammatically: it should more properly read “contains behaviour that could be imitated” (better conjunction). But that’s for another discussion. Can’t a lot of behavior that you see online be imitated — whether or not you even want to try and be like Jack Donaghy in 30 Rock or Luke Skywalker in Star Wars? This advisory sounds more like an offering to stand-up comedians than a warning to parents of young and impressionable children.

Parental advisories for Batman Begins (and many other movies) warn of “revealing clothing” and “dysfunctional relationships”. Whoa. But do kids really need to follow the adventures of the caped crusader in order to catch a glimpse of either of those mildly perilous phenomena? I’d say they’re more like blanket content advisories for 21st-century life.

Here’s one of Wikipedia’s several stern disclaimers. It isn’t inexplicit or vague in any way, but it does seem just a little over the top, if not perhaps tongue-in-cheek:

“USE WIKIPEDIA AT YOUR OWN RISK: PLEASE BE AWARE THAT ANY INFORMATION YOU MAY FIND IN WIKIPEDIA MAY BE INACCURATE, MISLEADING, DANGEROUS, ADDICTIVE, UNETHICAL OR ILLEGAL.”

* * * * *

Moving on from the (presumably) unintentionally inexplicit warnings, here are some spoof advisories that were designed for our entertainment. Warning: explicit content follows. (And I’m not being ironic; it really does.)

The musical show Avenue Q has warnings such as “PARENTAL ADVISORY: 60% adult situations and 40% foam rubber”, and “Not appropriate for children due to language and adult content such as full puppet nudity”.

Another show, Jersey Boys, offers this disclaimer: “This musical contains smoke, loud gunshots, strobe lights, and authentic, offensive Jersey vocabulary”.

Monty Python’s The Album of the Soundtrack of the Trailer of the Film of Monty Python and the Holy Grail contains this warning: “There is little or no offensive material [on this record] apart from four cunts, one clitoris, and a foreskin. And, as they only occur in this opening introduction, you’re past them now.”

One of the tag-lines for the 2008 movie An American Carol reads: “WARNING! This movie may be offensive to children, young people, old people, in-the-middle people, some people on the right, all people on the left, terrorists, pacifists, war-mongers, fish mongers, Christians, Jews, Muslims, atheists, agnostics (though you’d have to prove it to them), the ACLU, liberals, conservatives, neo-cons, ex-cons, future cons, Republicans, Democrats, Libertarian, people of color, people of no color, English speakers, English-as-a-second language speakers, non-speakers, men, women, more women, & Ivy League professors. Native Americans should be okay.”